Parklands Albury Wodonga acknowledge the Duduroa-speaking people as the Traditional Custodians of the lands now known as Huon Hill Parklands.

Rising 263 metres above the Murray and Kiewa floodplains, Huon Hill offers spectacular views of Lake Hume, the Kiewa Valley, the Alpine Region, Murray and Kiewa Rivers, and Albury and Wodonga cities.

Huon Hill is ideal for bushwalking, sightseeing, picnicking and photography. Come for an hour or stay the whole day. Huon Hill offers a variety of recreational experiences as well as look outs on Huon Hill overlooking the Albury-Wodonga region.

Size

238 Hectares

Views

Stunning panoramas overlooking Albury, Wodonga, Lake Hume, Mt. Bogong, Mt. Feathertop, the Kiewa Valley, Bonegilla, Baranduda Range, Table Top Mountain and the Murray Valley towards Corowa.

Landform

Steep rolling hills, some rocky outcrops

Classification

Recreation and conservation

The track names are native trees that are typical for this type of Box Gum Grassy Woodland area, an ecological vegetation community that is on the National EPBC list as Endangered:

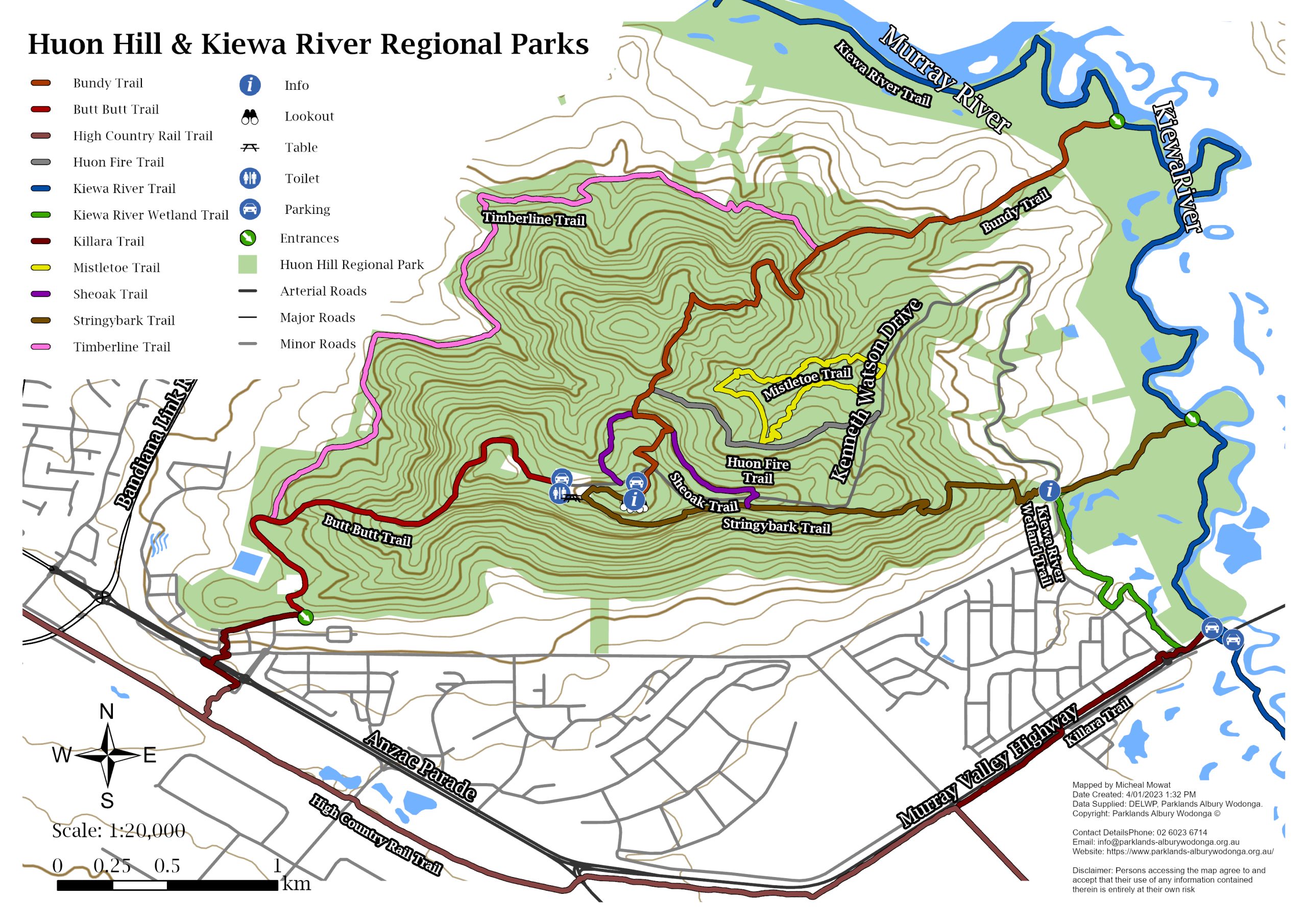

- Summit Track (200 metres)

- Bundy track (3km)

- Sheoke track (2.5km)

- Mistletoe Track (2km)

Click here for Trail Notes – Huon Hill

Access:

Huon Hill is to the east of Wodonga. Head out Thomas Mitchell Drive onto the Murray Valley Hwy and turn left onto Whytes Road (opposite the Wodonga Sale Yards). At the end of Whytes Rd turn right into Kenneth Watson Drive and this will take you to Huon Hill Parklands

Things to Do:

- Birdwatching

- Picnicking

- BBQ

- Short walks

- Long walks

- Photography

- Sightseeing

- Citizen Science

- On-leash Dog Walking

Facilities

- Walking Tracks

- Information Boards

- Seating

- Carparking

- Electric BBQs

- Shelter

- Composting Toilets

- Picnic Tables

- Lookouts

- Directional Cairn

Want to get involved? We’re always looking for volunteers and people with unique skills to help out whenever possible. Click the link below to find out more!

A long time ago (pre-1788)…

130 million years ago, the Murray Darling Basin was submerged under a shallow sea. The land mass began to rise out of the sea about 100 million years ago, causing the inland sea to flow back into the ocean in South Australia. It was this process that created what would eventually become the Murray Darling Basin and Murray River.

Ancient rainforests – buried under a sea of sand

Before the more recent changes to the flows of the Murray River, the river followed a much broader meandering course right across the valley floor. During winter and spring rain events, it covered vast areas of the land with water which carried large volumes of eroded silt, sand, and gravel.

The river regularly changed its course, breaking its banks and cutting its way back and forth across the floodplain, leaving ox-bow lagoons and wetlands in its path. These past river channels can easily be seen from Huon Hill lookout.

Over many thousands of years, the Murray River has transported the sediments from the slowly eroding eastern mountain ranges across its floodplains, eventually burying an entire forest of Australian Red Cedar and other locally extinct plants under 15 metres of sand. The rare Red Cedar, a relic of more wet and tropical climatic conditions, no longer exists above ground in this region. However there are still many examples of well preserved 40,000 year old Red Cedar timber buried throughout the Murray floodplain. Some of this was recently unearthed at a quarry on Gateway Island.

After European settlement, changes were quickly forced upon the Murray River and surrounding landscape. Broad-scale tree clearing and rabbit plagues in the 1800s contributed to catastrophic erosion events which rapidly increased sediment loads down the river. Then in the early 1900s, efforts to drought-proof the irrigation industry and provide secure water for towns downstream by damming the river also came at a great ecological cost.

Soils, topography and the dominant vegetation types

The plants we see today have evolved with the changing landscape and climate. The climate has changed from a wetter and cooler one, to the increasingly hot and dry warm temperate climate we experience today. With climatic changes, so too the plant life here has evolved from water and shade loving plant species to the hardier plants like eucalypts, hard-leaved shrubs, and drought tolerant native grasses.

Topography also has a big influence on plants. On the surrounding hills for instance, we have open grassy woodlands dominated by Hill Red Gum, White Box, and open grassy areas. Moving down to the lower slopes we have valley grassy forest dominated by Apple Box and Yellow Box. Then along watercourses we have plains of Grey Box and riparian woodlands of River Red Gum, as well as wetlands with unique and important water-dependent plants which act as nutrient filters and breeding nurseries for many organisms.

Not so long ago…

Murray River— lifeblood for people for tens of thousands of years…

The Murray River was the life blood of First Nations people throughout south east Australia for thousands of years, providing a bounty of food and resources which were able to maintain large numbers of people in numerous groups. We invite you to look at the landscape through a First Nations Australian’s eyes.

Majestic River Red Gums

See how they line the Murray and Kiewa River below. These trees were very important to First Nations peoples as their traditional uses included medicine, tools and implements, shelter, and supermarkets for food. Young leaves were crushed and boiled for steam baths to treat ailments and the gum was used for burns. Bark was used to make shields, water vessels, shelters, and canoes. A contemporary “canoe tree” can be found on the Kiewa Track. A bark canoe was carved from this River Red Gum tree using only stone tools in 2012.

The names given to places on this map gives some idea of how First Nations Australians view the landscape. Place names relate to the type of resources found there. For instance, Killara means “permanent water” which was important during the summer months when the Murray River and Mitta Mitta River used to dry up to little more than water holes. Baranduda meant “water rat”, a good place to go hunting, and Mungabareena meant “meeting place”. These names continue to reflect these resources, with Killara continuing to be a popular swimming hole in Wodonga and Mungabareena Reserve still a popular picnic and meeting place.

Dramatic changes since 1788…

After many thousands of years of First Nations Australians living in relative harmony with nature, Europeans arrived and made drastic changes in a very short time. Many changes to the landscape have been caused by a combination of forestry, agriculture, mining, river regulation, and urban development. The lookout platform story boards tell some of these stories.

This hill comprises Box Gum Grassy Woodland vegetation. This type of open country was common pre 1788 but has become a threatened ecological community. Today our region boasts a strong environmental record, with numerous Landcare, Friends and environmental groups and individuals all acting to reduce their impact on the planet and working to remedy the damage that has been done since 1788.

The first Europeans to see the Albury-Wodonga region

The explorers Hamilton Hume and William Hovell were the first to discover the Murray River at Albury on November 16th 1824. They initially named the river the Hume River, and inscribed their names and the date on two River Red Gums on the riverbank. The Hovell tree can still be viewed today in Hovell Tree Park, Albury. Albury Botanical Gardens have planted clones of the original tree at other historic Hume and Hovell sites around Albury – Wodonga.

Signs of First Nations occupation and early European settlement remain

There are many things from Albury-Wodonga’s history that have been long lost. However, many signs of First Nations occupation and past European settlement still remain, albeit sometimes less visible to the untrained eye. History buffs might be interested to see local historic sites such as:

- Yeddonba First Nations Rock Paintings and water holes at Mt Pilot

- The ‘Wiradjuri Talkback’ First Nations display at the Albury Regional Museum

- Numerous scar trees and artefact scatters along the main watercourses of the region

- Bonegilla Migrant Experience Heritage Park located at Kookaburra Point on the Hume Weir

- The Hume Weir wall and Old Tallangatta, the town that moved in the 1950s

- The Albury Railway Station – a building with great significance for the region’s history

Greening the Albury Wodonga Growth Centre

The vision – Create a ‘Great Inland City’

In 1973 the Albury-Wodonga National Growth Centre project was conceived and the Albury Wodonga Development Corporation established. It was a bold vision that involved three governments embarking on the building of a new city in the country. The aim was to decentralise Australia’s population, to attract people away from the cities that were becoming congested, even back then. Prime Minister of the time Gough Whitlam, the principal driver of the scheme, declared that “building cities is by far the most difficult, complex and majestic thing that people do.”

Murray Darling Freshwater Research Centre

The Albury Wodonga Corporation established the Peter Till Environmental Laboratory in the 1980s in an effort to study the local rivers and tributaries, and to monitor their flows and their chemical and biological condition to ensure that water quality did not deteriorate as the population grew. This laboratory was further developed and took up a Murray-Darling Basin-wide scope after Commonwealth investment created the Murray-Darling Freshwater Research Centre in 1986. This laboratory still operates today and continues to provide an ecological basis for the sustainable management of Australian surface waters.

Greening the Growth Centre—biggest reforestation program in Australia

Albury Wodonga Development Corporation planted over three million trees and shrubs, establishing their own nursery in order to produce 150,000 plants each year.

Emphasis was placed on putting trees and shrubs into key landscape connections like creeks and roadsides, in an effort to link the hills with the Murray and Kiewa Rivers, and create wildlife corridors. The main species used in the planting program included the eucalypt species of White Box, Red Box, Apple Box, Yellow Box, Red Stringybark, Blakely’s Red Gum, River Red Gum and Ironbark, as well as a variety of Acacias (wattles), native Cypress Pine and Drooping She-oak.

A lasting legacy— landscape scale conservation

Approximately 3,700 hectares of land was gifted to the community for environmental purposes. This included 1,100 hectares of environmentally sensitive corridors that were identified in three award winning threatened species conservation strategies: the Thurgoona and Albury Ranges Threatened Species Strategies and the Wodonga Retained Environment Network Strategy.

Community stewardship— Parklands Albury Wodonga

The Albury Wodonga regional parklands project was kick-started when Albury Wodonga Development Corporation transferred 1,720 hectares of land, valued at more than $4.4 million, into public ownership into perpetuity.

This new land was managed by Parklands Albury-Wodonga, an independent community organization. The best way to protect the environment was to get people to enjoy it and foster community stewardship. Better access was provided to bushlands and to the river environs. Parklands was a leading partner in several large scale environmental and recreational projects, including Huon Hill – Kiewa River, Wodonga to Corryong High Country Rail Trail, Gateway Island, Padman-Mates Park in West Albury and an interpretive centre at the former Bonegilla Migrant Reception and Training Centre.

Thank you to the regional community for investing in excess of $15 million in establishing the regional parklands.

Today…

After 14 years of significant landscape-scale conservation works to transform this cow paddock into a regional park, Parklands’ role at Huon Hill has changed. City of Wodonga formally took over the maintenance of this bush park in July 2010.

Parklands continues to implement environmental and recreation projects in partnership with the City of Wodonga. Parklands is also responsible for the crown land around the Huon Hill Lookout area. Interpretive Planning students from Charles Sturt University are currently reviewing the ten year old signage, as a number of other walking tracks have since been established.

There has been a significant community contribution towards the establishment of Huon Hill Parklands. This includes: road upgrading and sealing; by-pass lanes; car parking; composting toilets; barbecue and shelter facilities; lookout platforms; 7 km’s of walking tracks; fencing; signage and interpretation; revegetation on the slopes and gullies; and installation of 100 nest boxes in the Hidden Valley corridor for the threatened Squirrel Glider species.

Thank you to the Rotary Clubs of Wodonga, West Wodonga, and Belvoir for their significant financial and in-kind contribution towards constructing the rotunda and shelters. Other significant partners include Wodonga TAFE teachers and First Nations Community Development Employment Program participants who constructed the lookout platforms, compost toilet, and many steep and rocky fence lines.

In addition to hundreds of individual volunteers, groups include Workways staff, Australian Taxation Office staff, Wodonga TAFE staff, Hume Building Society staff, Murray High School students, Wodonga Catholic College students, Lavington Scouts, Border Bushwalking Club, Murray Valley Centre, Wodonga’s Youth Leadership participants, CVGT Green Corp teams, Personnel Group Green Corp teams, and National Environment Centre (Riverina Institute of TAFE).